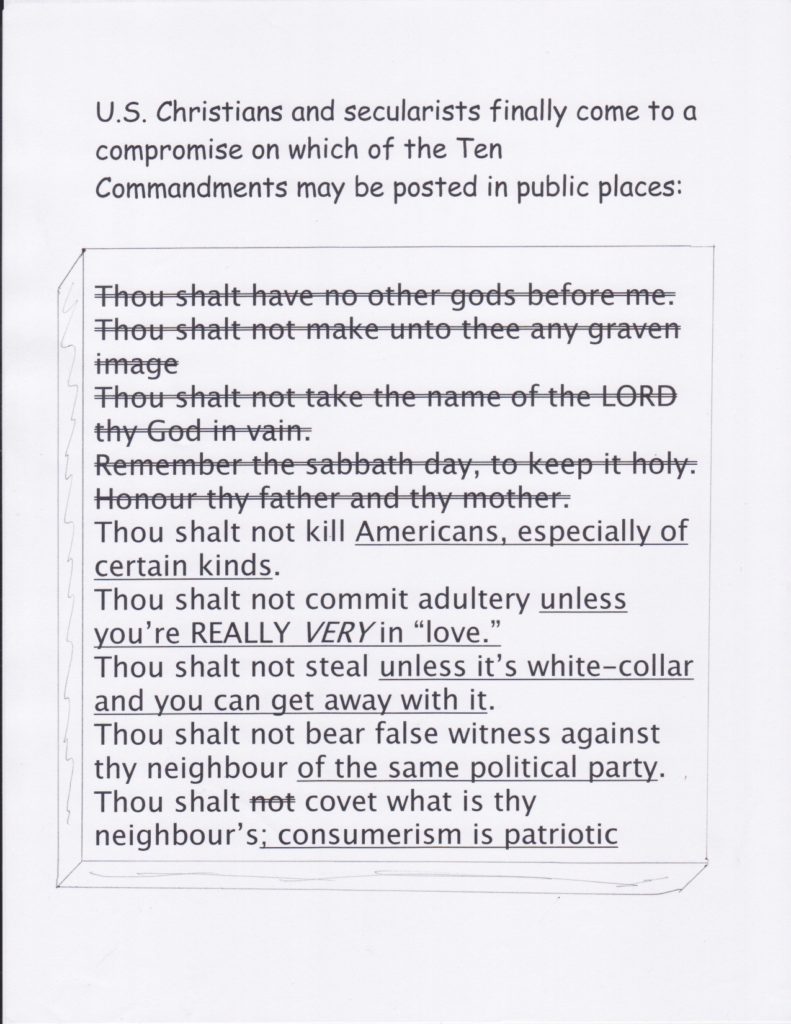

The Edited Ten Commandments

God’s commission seemed impossible to Moses, but God reiterated his call (Exod 6:28-30). Before sending him back, he addresses Moses’s fears.

Not only was God far more confident than Moses that Moses would be effective in his commission, but he assured him with strong words. Pharaoh, who considered himself a god, might not want to heed mortals. But as the true God’s messenger, Moses would speak to him as the voice of God, with Aaron being his prophet (Exod 7:1). (Contrary to the views of a few later confused readers, it is clear that God speaks figuratively in terms of Moses and Aaron representing him rather than being him; see v. 2.) In plagues announced through Moses, God would even strike the gods of Egypt (Exod 12:12; Num 33:4), including the household of Pharaoh himself.

Because God knows what he can do through us when he calls us, he can have confidence in his calling for us and our consequent effectiveness. Our effectiveness, of course, comes from him, and is limited to the sphere of our calling, which is not always “success” by the world’s standards. What matters is that it is success by God’s standards. God rarely calls people to do what we can do solely by our own strength; he delights to show his power through vessels that, on their own, appear weak and lowly.

But if such words gave Moses a sense of encouragement, God’s next words would remind him that more tests awaited. Yes, Pharaoh would send God’s people from his land (Exod 7:2). But first God would harden Pharaoh’s heart to not listen, so God could display his wonders in the land (7:3-4). Undoubtedly Moses, like most of us, would prefer for God not to harden Pharaoh’s heart; after all, softening his heart would make things much easier.

But the easier way is not always better. The Lord here declares his reason: Pharaoh’s resistance allows God to respond with signs of judgment—so that the Egyptians might know that he is the Lord (7:4-5; cf. 14:4, 18). God had raised up and allowed to remain this particular, resistant Pharaoh (9:16), and would continue to harden (cf. 4:21; 9:12; 10:1, 20, 27; 14:4) a heart that also chose to be hard (8:15, 32; 9:34).

When we face others’ resistance to God’s plans, we can take courage that God is sovereign, and also take courage that God has a purpose even in events that seem hard for us. For that matter, the delay would be helpful even for the Israelites, who also needed to face testing to learn that the Lord is God (10:2; 16:12).

God knew whom he had chosen; he knew what Moses could be better than Moses did. Thus Moses and Aaron obeyed his command to go again before Pharaoh (7:6).

The last post discussed how Exodus uses Moses’s genealogy (Exod 6:14-25) to underline the weak sort of vessel that God chooses to use. Exodus frames that genealogy with Moses’s fearful protest in the presence of YHWH: “I’m uncircumcised in lips; so how is it that Pharaoh is going to listen to me?” As with some other framing devices in ancient oral literature, this one is somewhat inverted, transposing the order of the two clauses (6:12, 30).

Because Exodus emphasizes the point by repeating it, it seems fair for us to do the same.

Yet the Lord had already answered Moses’s objection earlier. “I’m not a good speaker,” Moses protested, “and my mouth and tongue are heavy!” (4:10). “Who made a person’s mouth?” the Lord demanded. “I will go with your mouth and teach you what to say” (4:11-12).

Who are we to question God’s call? Who are we to evaluate by the world’s criteria? God will back up what he calls us to do. Some speakers who do not sound eloquent are nevertheless anointed by God in such a way that people’s hearts are changed. Eric Liddell did not have the best form, but God made him fast. Unlike George Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards was not the most eloquent speaker, but the Spirit could fall when he simply read a sermon. Natural gifts are a blessing, but for God’s call we cannot depend solely on them. We depend on the one who called us, and he can gift us in new ways as he chooses.

If God gives you ways to fulfill your calling better, take advantage of them. But don’t think that God cannot use you because you are too small. God uses especially those who know they are small. As mentioned earlier, someone once introduced Hudson Taylor, nineteenth-century founder of a very effective ministry to China, as a very great man. When Hudson got up to speak, he countered that he was a very small man with a very great God. He understood the ministry principle revealed in this passage.

Ultimately we are called to speak whether people will listen or not (as in Isa 6:9-13; Jer 1:17-19; Ezek 2:5-7; 2 Tim 4:2-5). Sometimes the fruit comes later (cf. Acts 7:58). It is not our role to predict which seed will bear fruit, but we can trust that it will always be enough; God’s message will bear fruit in its time (Isa 55:10-11; Mark 4:14-20, 26-29).

Jeremiah lived to see his land devastated and his people enslaved; yet a generation beyond him, God’s people recognized the truth of his message and never again turned to physical idolatry (2 Chron 36:21-22; Ezra 1:1; Dan 9:2). Paul lamented that all Asia—the place of his greatest ministry (cf. Acts 19:10, 17, 20)—had turned away from him (2 Tim 1:15). Yet his writings have shaped and challenged the church for two millennia.

Moses could not enter the promised land, though God did allow him to see it (Deut 34:1-6). The next generation, growing up under God’s revelation, apparently treated Joshua much better, but Moses faced opposition even from his own people. Yet God fulfilled the purpose for which he raised Moses up. We later see the same principle regarding David: he died, “after he had served God’s purpose in his own generation” (Acts 13:36). We should never forget that we are each only part of the story. Yet we can also celebrate the privilege that God has given us, that we do get to be part of his story, a story that will echo throughout the ages of eternity.

Whether our role seems to us big or small, let us fill that role with our whole hearts, and give all the honor to the story’s Author, to the Lord himself.

God calls us to serve his purposes and does not wait for us to figure out whether he might use us. God takes weak people and shows his glory by using us. Moses eventually learns this lesson, despite his protests, and so can we.

After Moses questions whether God’s call in his life is accomplishing anything fruitful (Exod 6:12), God simply reiterates his call (6:13). But then Exodus suddenly digresses to rehearse Israel’s genealogy up to Moses (6:14-25), before returning to the topic where the narrative started (6:26-30).

This genealogy includes only three tribes: Reuben, Simeon, and Levi. Why these three? They were the first three sons of Jacob by birth order, so this was the sequence in which one would recite genealogies (cf. Gen 46:8-11). The list in Exodus 6 stops with and fleshes out more fully Levi’s descendants (6:16-25) because that that family tree brings us to Moses, Aaron, and their kin.

But since the list will focus on Levites, why does it first briefly summarize the clans of Reuben and Simeon (6:14-15)? When we memorize something in order, sometimes it is difficult for us to recall it out of order. One accustomed to orally reciting a full genealogy of Israel might be accustomed to noting Reuben and Simeon (Exod 6:14-15) before reaching Levi (6:16-25).

Nevertheless, granted that point, an experienced narrator easily could have skipped them. At some point an editor could have removed this oral feature; why mention again Reuben and Simeon at all? The answer to this question might be related to our next consideration.

Why rehearse this genealogy here? Why not at the beginning of Moses’s story, like genealogies introducing Noah (Gen 5:3-32, esp. 32) or Abraham (Gen 11:10-30, esp. 11:26-30)? Maybe the narrator wanted to get listeners engaged in the story before digressing for a genealogy? After all, there was a genealogy in Genesis 46, toward the end of the Joseph story (and after the climax of its action), so it may have been too soon for another genealogy at the beginning of the Moses story.

But granted that a genealogy might not have fit best at the beginning of Moses’s story, Exodus does not even name Moses’s parents until this point (though his brother Aaron is already part of the story at 4:14). And if there was to be a genealogy, why specifically at this moment? And why does the narrative of Moses’s questioning frame this genealogy as a digression?

This genealogy, like its context, helps to depict in stark fashion how mortal and finite Moses is. Reuben, Simeon and Levi were all patriarchs who sinned grossly. They thereby forfeited their place of honor to Joseph, who received the blessing of the firstborn toward the end of Genesis (Gen 48:5; 49:4-7, 26). Moses and Aaron are mortals whose lives were set in wider kin circles of other mortals. That is, they are historically contingent individuals, dependent on and existing in a series of temporally limited generations in history.

In other words, who is this little Moses to question the big, infinite, eternal God? Probably to reinforce such a point, the narrative repeats what it was saying before it digressed. “This was the very Aaron and Moses to whom the Lord said, ‘Bring the Israelites out of Egypt by their hosts.’ They were the very ones who spoke to Pharaoh king of Egypt to bring the Israelites from Egypt—that was this same Moses and Aaron” (Exod 6:26-27). The Hebrew text seems emphatic.

God commanded small people to do a big thing; the big thing succeeded not because Moses and Aaron were so great, but because God is so great. God did make Moses increasingly into the servant that God was calling him to be, but Moses was a vessel, an agent, a messenger through whom God worked, and Exodus is emphatic about this point. He is to speak to Pharaoh what God spoke to him (6:29); that is what a messenger does. Messengers of kings can’t boast as if they are kings themselves; we cannot boast as if we originated the message. We are just messengers, agents of the one who sent us.

Moses himself would not have wanted it any other way; he was, after all, the lowliest, humblest man in the whole world (Num 12:3). That was one reason that God could use him. God uses the weak things of the world to confound the powerful (such as Pharaoh), that the honor might belong to the Lord himself alone (Isa 42:8; 48:11; John 5:44; 2 Cor 13:4; esp. 1 Cor 1:27-29).

We all know ministers who got messed up because they got big heads, forgetting where God had brought them from. Should God choose to use us because we are weak, we must never to forget he chose us as weak vessels (cf. Deut 6:10-12; 1 Sam 15:17). He gets the credit, and we have the privilege of watching what he does even through us.

Have you ever been in an impossible situation? But if you’re following the Lord’s plan, he’s got your back.

The Lord summons Moses to go back to Pharaoh, so that Pharaoh will let God’s people go (6:10-11). God does not promise that Pharaoh will comply on the next try, but he is sending Moses nonetheless. Already rejected by the Israelites at this point (6:9), Moses protests that this is an insane predicament. His own people have not listened to him, and does God think that Pharaoh will listen to him (6:12)? Moses is still not very persuaded; from the beginning, he has insisted that he is not qualified, and Moses probably does not understand why God is still not listening to Moses’s objections.

Moses reminds God that Moses cannot speak well (6:12). Moses had already explained this to God in 4:10, but now he uses even more shocking language. Moses literally describes himself as one “uncircumcised in lips.” Perhaps he evokes his previous resistance to God’s demand that he circumcise his son (4:24-26), or implies that his lips are like those of Gentiles. But it is probably simply a way of depicting his lips negatively, so that his speech cannot persuade Pharaoh, before whom ambassadors would present skillfully prepared speeches.

Many of us can probably sympathize with Moses. We can be grateful for communicators who provide slick, precisely-timed presentations, but most of us are not at that level. Some people have great content and are great communicators, but most of us think of ourselves as fairly average. Yet God chooses whom he wills for particular tasks. Many of Billy Graham’s jokes fell flat, but God commissioned him with a mantle of authority in evangelism that drew people to Christ. Some people gifted in healing are terrible preachers, and some who preach well do not have great track records with healing gifts. God has gifted me to write after thinking matters through, but I don’t think quickly enough to excel in debates. When God calls us to do something we’re not great at, we might still not be great at it. But it is something that God wants done.

Undoubtedly much to Moses’s dismay, the Lord simply reiterates his instructions (6:13), this time to both Moses and Aaron (the latter initially appointed to compensate, if need be, for Moses’s reticence to speak, 4:14). These instructions pertain to both resistant entities: Israel and Pharaoh (cf. 6:12). Moses and Aaron are to bring the Israelites out of Egypt—something humanly impossible for them to achieve.

Only the Lord can make that happen, and, from Moses’s erroneous perspective, the Lord’s meddling so far has only made things worse. Pharaoh will surely not listen to YHWH. But Moses does not yet understand what YHWH can do to persuade Israel, Egypt, and, last of all by God’s design, Pharaoh himself. Along the way, Moses himself will come to understand. God’s instructions do not always make sense to us, even in Scripture, but God knows exactly what he is doing.

Moses faced opposition not only from Pharaoh but even from his own people. We should not expect all our service for the Lord to be easy. When you face discouragement and doubt as to why God would call you, remember that you are not the first to face this.

Recapping some of the character development so far in Exodus (in the earlier Bible studies):

(1) Moses. Moses seems perfectly understandable from a human point of view. Imagine that you have heard of the God of your ancestors, but you’ve never seen a miracle. Your people have been enslaved by another people who claim that their gods are much stronger. But you are now old and you have made peace with your life, giving up on youthful dreams of changing things. Suddenly the God of your enslaved people appears to you and commissions you and ruins your satisfied life. You’re told to confront the most powerful leader in the world, who claims to be backed by lots of powerful gods. God gives you some signs, but these are fairly low-level magic tricks as far as the leader’s own paid signs-workers are concerned.

Nevertheless, under duress from your ancestors’ God you confront the powerful leader and give the best signs that you’ve got. Sure enough, he’s not convinced, and things get even worse for your people. Your own people realize things are worse and turn on you. Do you think you would be happy with your commission?

How many of us are ready to give up sharing our faith, or praying for someone, etc., when something does not go the way we want? Do we really have much more faith than Moses? Before long, Moses does grow in faith (although his people take a lot longer). That means that there is hope for us too. We can learn from the example of Moses because many of us are a lot like him.

(2) The Hebrew foremen. The Hebrew overseers also are perfectly understandable from a human point of view. Say someone comes to you promising deliverance and working a few tricks. You trust them and stick your neck out, but then you get burned. Things get worse for you rather than better.

We all know there are false prophets, and we’ve all been burned by sales gimmicks that turn out to have strings attached. Once burned, twice shy, as the saying goes. Moses, who has been away for years while you have been laboring as slaves, confronts Pharaoh. And as a consequence, you get loaded with more work and eventually get whipped. Would you still trust Moses? Of course, Hebrews have less excuse for their unbelief after the plagues start, but as of Exodus 6, you can see why Moses is still in the doghouse with his people.

The Hebrew foremen are a reminder to us of our own need to trust God’s plan beyond what we can see or even be sure about on a human level.

(3) Pharaoh. It might be harder to imagine Pharaoh’s point of view. If you’re arrogant enough to think the universe revolves around you, as Pharaoh presumably did (with the encouragement of his supporters), you probably wouldn’t be reading Bible studies or devotionals. But imagine somebody who from childhood has been groomed to believe that his destiny is to rule the world’s greatest empire. The gods supposedly support this, and Pharaoh himself is supposedly divine.

You think that the pitiful deity of the Hebrews has let them stay in slavery for generations. Thus he seems weak, in contrast to the splendor of Egypt’s gods displayed in monuments and artwork all around you (never mind how much of it was built by slaves and other conscripted workers). The only way to answer impudence and laziness is to crack down. Given his context, Pharaoh’s incalcitrance is not too unbelievable. It is nevertheless misinformed and deadly.

The narrative focuses especially on Moses; he is the protagonist with whom we are most invited to identify. The main driver of the action throughout, however, is a different character: YHWH. YHWH works, sometimes behind the scenes and yet now in often obvious ways, to fulfill the promises he made long ago to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. He doesn’t stoop to speak to arrogant Pharaoh directly; he raises up instead a descendant of the patriarchs (also a descendant of Levi, who with Simeon was not a particularly nice guy in Genesis). It’s God who stretches Moses and proves that God was right all along in calling him.

It’s God who predicts Pharaoh’s obduracy, and who shows himself more powerful than Pharaoh’s gods at each step (cf. Exod 12:12). (At the same time, he shows himself more merciful than Pharaoh in allowing reprieves each time that Pharaoh backs down, until Pharaoh reneges on his word each time and escalates the conflict.)

It’s God who has the long haul planned out, when his servants are ready to give up in the short run. We don’t imagine things from God’s point of view, but we can see God’s plan unfold in Exodus. Indeed, we already see part of it promised in Genesis.

When the world and your own life seem out of control, remember that God has a plan that’s bigger than we can see from our finite, time-bound perspective. That’s not an excuse to stay in slavery or to be content with injustice. It is a challenge to grow in faith and cooperate with God’s plan to change things, even when that plan extends far beyond what we can see. Let’s be ready for whatever God calls us to do. And most certainly, let’s be obedient to what God has already called us to do, sometimes individually in prayer, and always, corporately and individually, in his Word.

In Exodus 6:6-8, God not only promised liberation from slavery, but also a land of their own in which they could be free. From the start, then, God’s promise had envisioned the completion of their deliverance. What he began in their deliverance, he would complete. (The New Testament later depicts our present experience along the lines of a new exodus: God has redeemed us through Jesus’s death at his first coming, and now we await our promised full inheritance at his return.)

But in 6:9, the Israelites didn’t believe these promises. This was because they had suffered so long, and they hadn’t yet seen the deliverance that Moses had already promised. So why should they trust the promise now? The answer is that God is trustworthy; but their hardships were so severe, and their most influential experiences with God so distant in the past, that they could not see past what they were experiencing.

Sometimes we don’t know why some promises take so long to fulfill; why did Israel suffer so long in slavery? Sometimes reasons for delay, including perhaps in our future inheritance, might lie with us (cf. Matt 24:14; Rom 11:25-26; 2 Pet 3:9, 12). Sometimes, however, they lie also in the fact that God is orchestrating matters on a wider scale. In the case of the exodus generation, the land that was going to be theirs belonged to somebody else; only after generations of mercy was God terminating the other peoples’ right to it (Gen 15:16). (See http://www.craigkeener.org/slaughtering-the-canaanites-part-i-limiting-factors/; http://www.craigkeener.org/slaughtering-the-canaanites-part-ii-switching-sides/; http://www.craigkeener.org/slaughtering-the-canaanites-part-iii-gods-ideal/.) Some complain that God is slow concerning his promises (2 Pet 3:4), when sometimes he is patient for the sake of delaying judgment (3:9).

Moses conveyed God’s promise to his people, but because of their suffering they did not listen (Exod 6:9). In today’s language, their hardship seemed to them more real than his promise. God does understand that hardships can break our spirits (cf. Prov 18:14; Mark 14:38; Luke 22:45), and he is near the brokenhearted (e.g., Ps 51:17; Matt 5:4). But Israel was starting on a path of unbelief and ingratitude in which they kept persisting even after seeing his signs that would deliver them. Eventually this would lead to discipline and would nearly lead to God abandoning them (e.g., Exod 32:10). At this point, however, he remains patient.

Often it’s hard for us to see far beyond our pain. God is faithful, however. As we often say in the Black Church, “God may not come when you want him to, but he’s always right on time.” God’s promises don’t always happen when we want them to. God’s blessings often don’t come the way we want them to. But God is worthy of our trust, and we can be sure that, in the end, he always has his people’s best interests at heart.

Without the promised land, deliverance from slavery would have been incomplete. Former slaves could not maintain their freedom in Egypt, and apart from direct divine sustenance could not survive in the wilderness. They needed a land of their own.

Thus, after announcing his people’s deliverance from slavery in Exodus 6:6-7, God announces a way for them to live independently, promising their own land (6:8). In contrast to their seminomadic, patriarchal ancestors, the Israelites were now too many to subsist on their own only as pastoralists grazing their flocks on the countryside. But whether pastoralists or farmers, they needed land; and for their agrarian society, land would be capital.

In my country, we saw the limitations of officially ending slavery without providing former slaves a means to work. Originally they were promised “forty acres and a mule,” but that promise was not kept. After the official end of U.S. slavery, many former slaves were kept in perpetual bondage as sharecroppers because ultimately they did not own their own land. In an agrarian economy, one must own land or depend on others for work. God was not just ending the Israelites’ official enslavement and then leaving them impoverished and subject to oppression, what many former slaves “freed” in the United States initially experienced.

From the start, then, God’s promise had envisioned the completion of their deliverance. What he began in their deliverance, he would complete. Today there is much debate about the Israelite conquest (more about Israel’s period of conquest than about conquests by ancient empires, because Israel’s is better known to us). (See limiting factors; switching sides; God’s ideal.) But the exodus without the conquest would have been what the Israelites themselves feared after the exodus: “Why did you bring us out of Egypt, to kill us and our children and livestock with thirst?” (Exod 17:3). God planned a full deliverance for his people, although in the ways used among nations in that day, not in the ways to be used by Jesus’s followers today.

What usually gets our attention is that God delivers us out of trouble. But God has a bigger destiny for his people than just getting us out of trouble. He brings us into relationship with himself. As part of his covenant with Israel, God said, “I will take you for myself for a people, and you will know that I am YHWH your God” (6:7). The covenant relationship meant that YHWH was their exclusive God and they were YHWH’s exclusive people.

The Hebrew expression translated “take for oneself” was often (though not exclusively) used in relation to taking for oneself or for one’s son a wife (e.g., Exod 6:20, 23, 25, in this context; Gen 11:29; 12:19; 21:21; 24:3-4; 38:6), with whom the husband would become one flesh, a new family unit (Gen 2:24). The term for “knowing” here was used for many things, but among them was marital intimacy, something later prophets deemed a fitting image of the covenant relationship with his people that God desired (Hos 2:20). Israel’s greatest privilege would be a special relationship with the living God.

They would know God specifically as the God who delivered them from their hardship in Egypt (Exod 6:7). We don’t know God just in an abstract way, but as the God we have met in our experience with him, especially in foundational acts he has performed. When the now-famous mathematician Blaise Pascal had a dramatic encounter with God, he described it this way: “FIRE! God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob, and not of the philosophers and savants!”

Nothing against philosophers and savants, but if I had to choose between studying about God and meeting him in person like Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, I would definitely go for the latter. They were most likely illiterate in terms of the writing of the time, which was mostly confined to scribes. If you’re reading this, you’re not illiterate, and since I typed this myself (I didn’t use voice recognition software), neither am I. We can study and have a personal experience with God. But again, if I had to choose, I would choose with Blaise Pascal. Nothing matches the experience of God.

The Israelites experienced God’s dramatic deliverance in the exodus. God’s self-revealing acts in history didn’t stop there. God has now revealed himself climactically in the cross and resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ, a specific, concrete act in redemptive history. We who entrust ourselves to Christ have his Spirit working in our hearts, enabling us to call God, “Father!”

Moses complains that the Lord has not kept his promise (5:22-23; note last week’s post); the Lord responds that now Moses will see what the Lord will do to Pharaoh, forcing him to drive God’s people out of Egypt (6:1)! If Moses is already doubting God’s promise, this renewed promise may not sound very encouraging. (Promises! Promises! And now the promise that the Egyptians wouldn’t even want them there anymore.)

But the Lord reaffirms his promise to bring his people out of Egypt not only in 6:1 but also in 6:6-8. In the intervening verses, God explains why Moses can trust this promise. The Lord had not tricked Moses and the people, promising something and then hiding, as it appeared to Moses (5:22-23). He was the God of their ancestors, who appeared to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob just as he had appeared to Moses (6:3). He had covenanted with those ancestors to give Canaan to their descendants (6:4), so he could be trusted to fulfill that promise now (6:8). The Lord had already spoken much about being the God of the patriarchs (3:6, 15-16; 4:5). But although Exodus already tells us that God had remembered his covenant with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (2:24), this is the first time that the text tells us that Moses heard that essential detail.

Moreover, the Lord was doing something even greater now than he did in the time of their ancestors. He had revealed himself to the patriarchs as El Shaddai, but only now was he revealing himself by his personal name YHWH (6:3). Theologians are right when they point out that God’s self-revelation in Scripture is progressive. Some might want to complain about new revelation with the coming of Jesus and what we call the New Testament, but new revelations happened periodically through the history of God revealing himself to his people.

More problematic is what precisely this passage means by the Lord not revealing himself by this name to the patriarchs. After all, the Lord does use this name for himself earlier; particularly noteworthy, compare Gen 15:7, where God says to Abram, “I am YHWH, who brought you out of Ur of the Chaldeans, to give you this land to possess it,” just as now God would bring them out of Egypt to possess the promised land (Exod 6:6-7). Likewise, compare Gen 28:13, where the Lord declares to Jacob, “I am YHWH, the God of your father Abraham and the God of Isaac,” and again promises the land to his people. (Certainly the phrase, “I am YHWH,” does recur much more frequently after this point; see Exod 6:6, 7, 8, 29; 7:5, 17; 10:2; 12:12; 14:4, 18; 16:12; 20:2; 29:46; 31:13; and still more frequently in Leviticus, in 11:44-45 and regularly in 18—26.)

Scholars thus have long debated what Exodus 6 means by YHWH not using this name for himself with the patriarchs. From a narrative perspective (that is, understanding the narrative in its final form), at least two options in particular commend themselves. One is that the stories in Genesis where YHWH identifies himself by this name were updated in light of this new revelation; after all, almost no one argues that the stories were written down before Moses’s day. They use the language of the fuller revelation available to them, the way Christian preachers today might speak of Jesus in the Old Testament.

Another option is that in Moses’s day YHWH is now revealing what it means for him to be YHWH: as “I am” (ehyeh; Exod 3:14), YHWH is eternal, and so does, in his time, fulfill his promises made generations earlier.

Not only had YHWH made a promise to their ancestors, but now was the time that he was revisiting that covenant. He was acting not only because of his covenant with their ancestors, but because he had heard his people’s groaning (6:5). The Lord acts both because of his covenant faithfulness and because he is compassionate and gracious, moved by the needs of his people and their cries. Thus he is compassionate, gracious, slow to anger, and full of covenant love (chesed) and covenant faithfulness (emeth, 34:6).

The Lord had already told Moses that he had heard his people’s suffering (3:7), but in 6:5 he reiterates this point. Often (thankfully for us), God encourages us with reminders of his faithfulness, even before we get to see the fulfillment of all his promises. (Those of us who get discouraged can hear his reaffirmations as often as we choose, provided we have Bibles and hear its message in context.) The ultimate consummation of his promises await Jesus’s return, but we have enough testimony from the past, and often signs in the present, to keep us going.